As I wrote about in the previous essay, Hitchcock’s Vertigo (1958) is a movie that gives us an almost mystical sense of San Francisco, but we eventually find that the apparent supernaturalism is all a ruse. Regardless of the twist, we are given a landscape that is definitive in its beauty. But thankfully for spectators, it turns out that Vertigo is in no way definitive, but just one of many examples that show the sometimes hypnotic vibrance of the city. Hitchcock’s film is very conservative in relation to the more countercultural aspects of cinema at the time. James Stewart and Kim Novak both starred in another film that was released six months later, which shows their romance in context to beatniks and bongo drums, albeit in Greenwich Village of New York City. Bell, Book, and Candle (1958) shows that the mainstream film industry was aware of the bohemian style of the time, although their portrayal of it seems more like a parody than a genuine depiction. Hitchcock completely overlooks this aspect of San Francisco’s population at that time. Just down the street from Scottie and Midge’s (Barbara Bel Giddes) apartments in Russian Hill, we would find North Beach, one of the world capitals of Beat culture, but we would never know that by watching Vertigo. As the avant garde strengthened in the 1960s, and Hollywood redefined itself into New American Cinema at the end of that decade, Hitchcock’s classic formalism began to wane in influence. The avant garde is not often discussed, overlooked in relation to more narrative countercultural cinema. For the purposes of this writing I will focus on three short films that all give us radically different, but equally compelling depictions of San Francisco--The End (1953) directed by Christopher Maclaine, Kenneth Anger’s Invocation of My Demon Brother (1969), and George Kuchar’s A Reason to Live (1976). All of these movies show us the supernatural qualities of San Francisco, while also--like Vertigo--revealing a dark side of the landscape, which serves up a list of utopian fallacies.

Among Christopher Maclaine, Kenneth Anger, and George Kuchar, the first of the three is the least known. Anger and Kuchar remain icons of the underground, while Maclaine gets a bit lost in the beatnik fray, perhaps because he only made four short films. His legendary influence cannot be understated. In an interview found in Radical Light: Alternative Film and Video in the San Francisco Bay Area, 1945-2000, Stan Brakhage states, “I know that the earliest he [Maclaine] was heard of, and became at all a figure, would be before my time, in the Beat period of San Francisco. He was then known as the Antonin Artaud of North Beach. To get such an appellation in such a town at such a time, he had to have been already far gone in [performing] disturbing antics.” (56) Brakhage--one of the greatest American avant garde filmmakers in his own right--recalls his experience at the premiere of The End in 1953, “I sat there because I was fascinated. I wanted to see every frame… Meanwhile, all around me, people were throwing things at the screen, and at each other, and at the floor. I was just trying to pay no attention to the riot…” (56) Maclaine’s film received a similar reaction to Buñuel and Dali’s Un Chien Andalou (1928), which sparked a riot in Paris 25 years earlier. Brakhage says of The End, “It certainly changed my whole life.” (57)

The End is a short film just over a half hour long, with a voiceover leading us through the last days of six different people. The images are not synchronous with the sound, but a heavily edited mixture of shots from around San Francisco. The characters occasionally show up in the sequences which the voice over dedicates to the others, creating a sense of confusion if seen only one time. The End is a challenging film, but it is difficult to imagine a crowd being so upset by it as to yell and throw chairs. The voiceover is not god-like exactly, but all seeing. The End is a spiritual film in that the voiceover suggests that fate is real. Our narrator delivers the lines in a deflated, disinterested way that might occasionally remind us of the protagonist from a novel published just a few years before--Holden Caufield of J.D. Salinger’s Catcher in the Rye (1945-6). The characters of The End talk of “grown up children”, and the desperation below the surface of mundane, adult life. There is also a very apocalyptic feel to Maclaine’s film. It is bookended by shots of nuclear mushroom clouds--“The world will no longer exist after this day.”

As much as The End universalizes human experiences of monotonous melancholia and anxiety, the movie is still very much set in San Francisco. We see an extended shot of a seagull in the fog, probably near Land’s End. We know Maclaine and cinematographer Jordan Belsen went out that way because there are also shots of the Diana the Huntress statue out near the Sutro Baths. Like in Vertigo, we see shots of The Palace of Fine Arts. The camera goes downtown, with shots of the Powell and Market cable cars, and a homeless man sleeping on an Embarcadero sidewalk. Perhaps the most iconic visual indicator of San Francisco is shot on an unnamed street. We see the diagonal angle of the city's hills, as a man walks up and down, playing with a yoyo in slow motion. The narrative says, “Dear friends, do not panic, there is very little time left, be peaceful. Let us hurry.”

Living up to his moniker, “The Artaud of North Beach”, Christopher Maclaine ended up very much like the French theater performer/producer--dying in a mental hospital. Brakhage describes the psychiatric institution as in the middle of the city, on the same block in North Beach where you would find City Lights Books. Maclaine was allowed to walk around the block once a day in his bathrobe, mind burnt out from too much speed. In The End he captured the mystical, foggy spirit of the city, as well as the murky, depressing side. Desperation, madness, suicide, and murder are part of the landscape as well, back then and now. Although immensely different movies, The End shares these qualities with Vertigo. We see these themes in the same setting the next decade, when Kenneth Anger showed up in town and moved into the William Westerfield House in Alamo Square.

It is surprising to find out that Anger lived in San Francisco for only a few years, as his influence and vibe manifested in various ways. His commitments to the occult, queer living, and cinema woven together into an entirely unique form of expression. The Magick Lantern Cycle began in the 1940s and went into the 70s, with particularly notable titles including Inauguration of the Pleasure Dome (1954), Scorpio Rising (1964), and Lucifer Rising (1972). The movies clash with contradictory elements, which spectators can either find repellent or engrossing. There is a decadence and hedonism to Inauguration of the Pleasure Dome, which belies a thrifty working class aesthetic. These people may just be playing dress up in someone’s apartment, but they are also transporting us to other eras and locations. If viewers have a background in Thelema and Aleister Crowley, Anger’s work is probably easier to follow. Otherwise it can be perplexing, but nevertheless intoxicating. In Scorpio Rising, the use of relentless pop music on the soundtrack is a practical choice, in that they didn’t have to record sync sound, but it also produces brilliant contrasts with the imagery of a hypermasculine biker gang. As I detailed a couple months back, punk rockers of the 70s used the swastika in an ambivalent fashion, but even before them, there was Anger and his motorcycle muses. This is made even more complicated as the symbol is also used in a historic and occult sense, before it was co-opted and ruined by The Nazis. Scorpio Rising gives us the unlikely marriage of astrology and leather in what amounts to a youthful, queer party movie.

Anger left his mark on San Francisco with Invocation of My Demon Brother, a ten minute short from 1969. Mick Jagger did the soundtrack with a Moog synthesizer, and by the sound of it, he was probably stoned and never learned how to use the thing. But the noisy dissonance is not necessarily bad (if searching for this on YouTube or elsewhere, be sure to find it with the original soundtrack, as a number of other people have uploaded it with unofficial audio). The movie has a lot of the same things as Anger’s previous work--eroticized, nude men, drugs, partying, and occult rituals. Much of it was shot at the Westerfield House, a sprawling Victorian building full of countercultural shenanigans. We see dudes jamming out and smoking weed from a skull. An albino with rapid eye movements. Fetishized tattoo close ups. A dead cat. The Death tarot card. And Anton Lavey, founder of The Church of Satan. Where Inauguration of the Pleasure Dome tries to make the performers otherworldly or from historic eras, Invocation of My Demon Brother is very much set in the late 1960s. It ends with a stop motion ghoul descending a flight of stairs and presenting a sign that says, “Zap, you’re pregnant, that’s witchcraft.” It is one of the most memorable moments of Anger’s oeuvre, specifically because he has no clear explanation. It evokes acts of procreation with witchy spells, or perhaps it is suggesting that those exposed to this cinematic ritual have seeds of the occult planted in their minds?

The movie is notable for the cultural figures involved. It is worth thinking about Jagger’s involvement in context to Anger’s open queerness. It was just a year later that the Rolling Stones singer appeared in hallucinatory queer sequences of Nicholas Roeg’s brilliant Performance (1970). Bobby Beausoleil--best known for his involvement with The Manson Family and the murder of Gary Hinman--plays Lucifer in the film, but ended up stealing much of the footage and burying it somewhere on The Spahn Ranch in Topanga Canyon. After his conviction and imprisonment, Beausoleil and Anger reached an understanding, which led to the former composing the soundtrack to Anger’s film Lucifer Rising. Perhaps the most San Franciscan cameo of all is Anton Lavey, who lived in the black house out in The Richmond, not far away from the Westerfield House. He was an iconoclastic figure of the time who presented ideas that were quite different from the blind, hippie fixation on peace and love. The reason Invocation of My Demon Brother works so well is because all of these real life characters--including Anger himself--projected highly dramatic emotions and performances, both in front of the camera and elsewhere.

By the early 1970s, underground filmmaker George Kuchar moved to San Francisco after gaining a cult following in New York City, for the odd short movies he made with his twin brother Mike. His work as a professor at The San Francisco Art Institute ensured that his influence, humor, and vivacious love of cinema permeated the city and whatever far off points the alum traveled to. Much like Maclaine and Anger, the Kuchar brothers made films that were full of fantasy, deviance, and drama. Perhaps what the siblings additionally offered was humor and lack of pretension. Kuchar filmmaking explored a love/hate relationship with cinema, where they aspired to the highest melodrama, while also dragging it into the self-dubbed “cinematic cesspool”. George and Mike are some of the first DIY filmmakers to ever pick up a camera, and the magnitude of their inspiration is impossible to quantify today. It is estimated that George made 400 to 500 short films in his career, many of which were produced with the help of his students in the Electrographic Sinema class. To choose only one title in order to define the filmmaker is an impossible task, but for the sake of this writing contextualizing Kuchar within the San Francisco landscape, we will focus on A Reason to Live.

Made in 1976, the twenty-five-minute experimental melodrama focuses on Vince (Curt McDowell), a soul-searching man who is involved with various women. The dialog and music are so over the top that it is simultaneously funny and jarring--melodrama has the ability to affect our emotions even if we know it is completely ridiculous. Vince sneaks away from his girlfriend (Marion Eaton) to meet up with his secret lover Chi Chi (Robbie Tucker), but Chi Chi falls down one of San Francisco’s very steep hills before they are able to meet up. Disillusioned, Vince goes to see his sister Julia (Maxine Duff-Davis), who is in a dire situation herself, having just tried to commit suicide by swallowing pills. Vince decides to go to Oklahoma, where he is killed in a tornado. Julia eventually succeeds in killing herself in the tub. The notable visual structure and theme revolves around the weather. Many ethereal shots of San Francisco’s fog punctuate the story. Vince has a keen interest in clouds--cumulus, nimbostratus, altostratus--leaving the city’s melancholy beauty for the ones he desires in Oklahoma. All the sprawling shots from the middle of the country make The Bay Area seem even that much weirder. After Julia’s first suicide attempt, she talks to her neighbor Nora (Marion Smith), who tells her, “The fog is coming to us. It will give you strength.” In the end, it does not. This quality of San Francisco's climate is not supernatural, although its residents want to believe that it is. While highly entertaining and memorable, A Reason to Live turns out to be immensely grim.

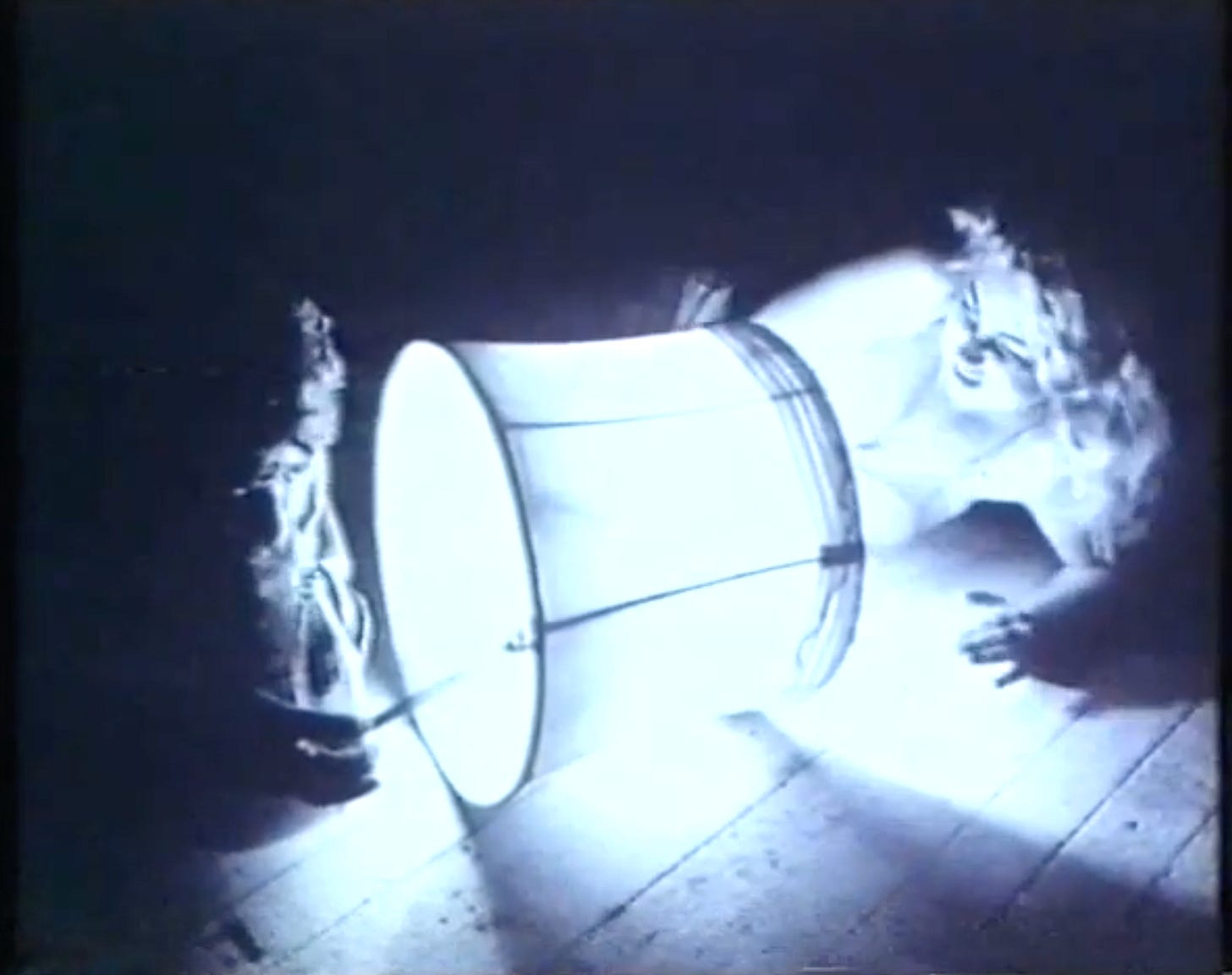

The End, Invocation of My Demon Brother, and A Reason to Live all toy with the potential magic of the city they take place in, but ultimately they all reveal that San Francisco is sobering and depressing as anywhere else. We see fascinating examples of the landscape, but also the dark side of the place and the people who inhabit it. The End is an existential meditation on the desperate futility of life, supplemented with fascinating visual metaphors. Invocation of My Demon Brother is about liberation through the occult, and a sense of chaotic rebirth. A Reason to Live ends up being a story of hopelessness, although following along as a viewer is an exciting process. So many people come to The Bay Area with the hope of finding happiness, a sort of California Dreaming as the song goes. But more often than not, the city turns out to be a sleazy delusion full of capitalist excess and anxiety. Much like the lamp knocked to the ground as Vince and Julia commiserate in her apartment, people are attracted to the city like an insect to a lightbulb. But this simplistic wonder is dangerous and easily extinguished.

Anker, Steve, Kathy Geritz and Steve Seid, Editors. Radical Light: Alternative Film and Video in the San Francisco Bay Area, 1945-2000. University of California Press, 2010.